Insulin is perhaps one of

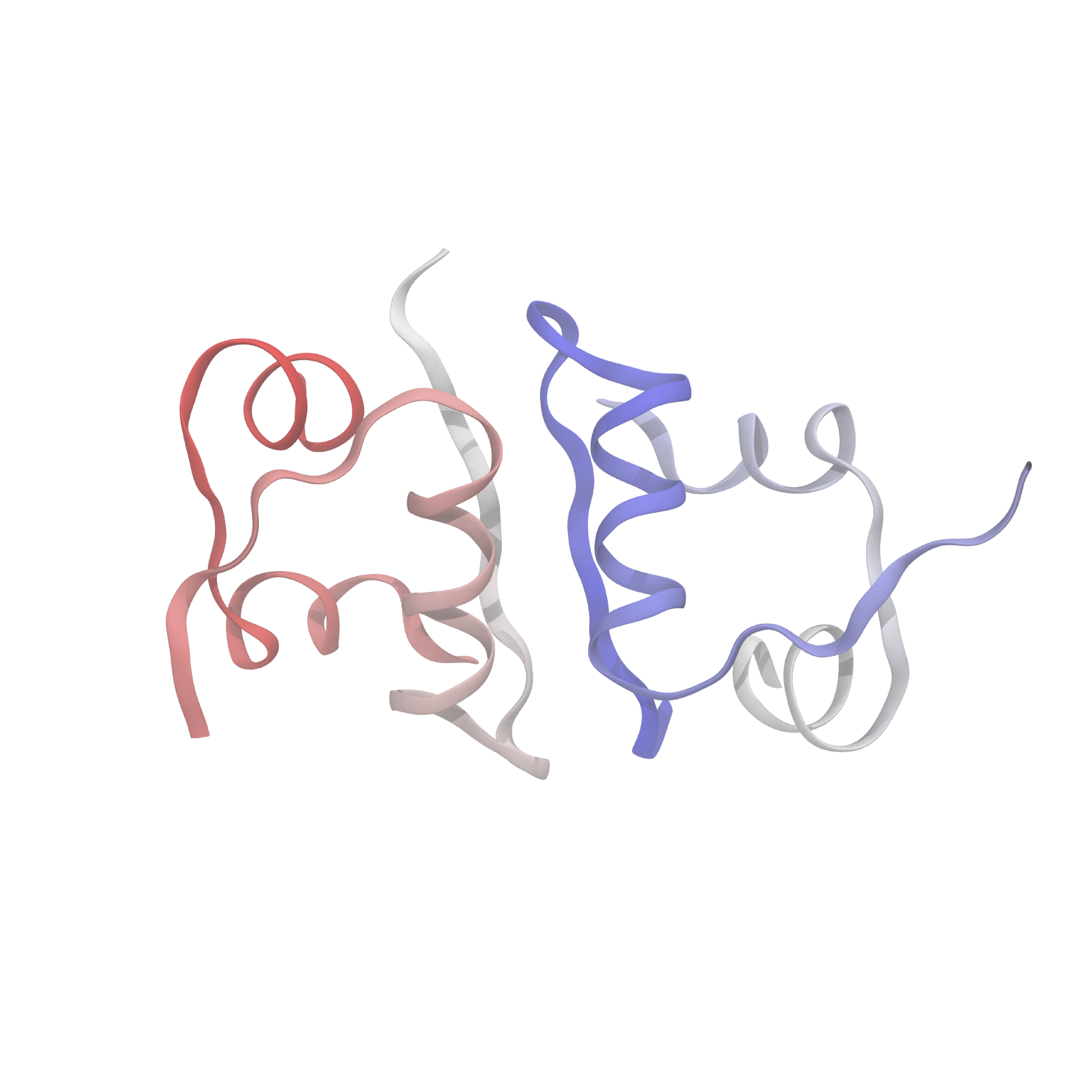

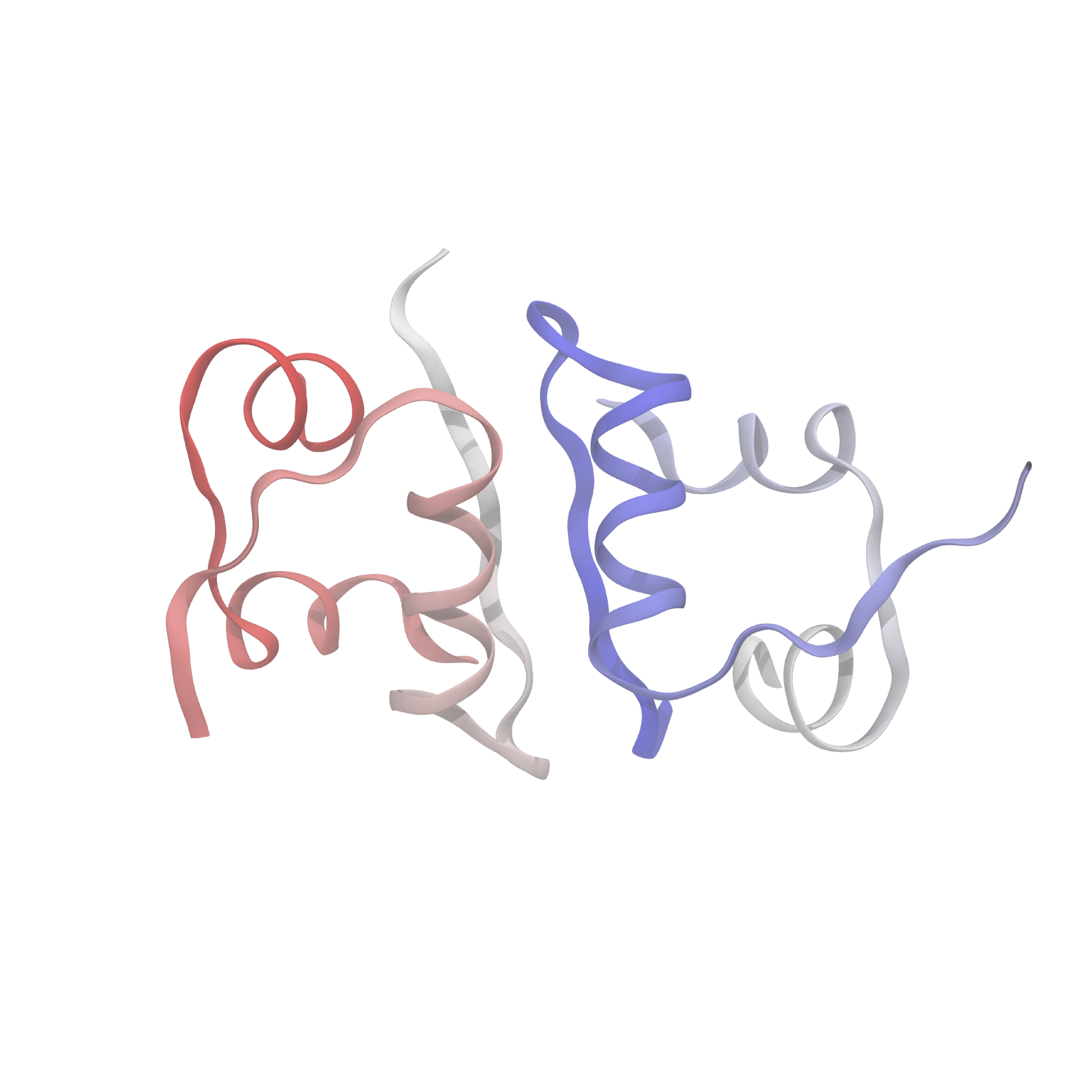

What's known today (and relevant for what I'll discuss here) is that the insulin molecule consists of two polypeptide chains, labeled A and B, with 21 and 30 amino acids, respectively. These two chains are held together by disulfide bridges between the A7-B7 and A20-B19 residues. Below is an image of the structure, displaying several secondary features of interest. Of particular note are the alpha-helices and beta sheets which form the monomer-monomer interface.

In the body, insulin is stored as a hexamer, which dissociates first into dimers, and then into monomers, which are the active form that bind to insulin receptors. The equilibria between hexamer, dimer, and monomer turn out to be essential for maintaining the correct balance of active insulin in the blood, and hence many therapeutic formulations aim to alter these equilibria in predictable ways. For example, several fast-acting insulin variants destabilize the dimer in order to favor formation of the monomer. Despite the decades of pharmaceutical reserch on insulin and its therapeutic analogues, it's not entirely clear still how these variants actually affect the hexamer-dimer-monomer equilibria and hence the timescale of activity.

In many ways, the dissociation and association of insulin is a prototypical reaction in biochemistry: we frequently want to understand protein-protein interaction at both a macroscopic (e.g. binding coefficients) and microscopic scales (i.e., which residues are involved) In fact, the dissociation from insulin dimer to monomer is conceptually simple since it involves two partners which are identical, as well as an extremely well-studied protein system. Although the macroscopic features of insulin dimer dissociation can be (relatively) easily measured through experiments, the microscopic features are much more difficult to probe using conventional techniques.

At heart, we care about understanding the sequence of events which cause a dimeric insulin molecule to spontaneously separate and break into two monomers. This process, though simple enough that you could describe it in a sentence, requires many things to happen correctly all at once. Consider the animation below, which shows only the interfaces in color (the aforementioned beta sheet in cyan and the alpha helix in magenta). From this short movie, it's rather entirely unclear what is occuring as the two monomers move apart. Is it the specific motions of sidechains at the interface? Is it water molecules (not pictured here, but essential for any biological process) invading the monomer-monomer surface? These are the types of questions we seek to answer and that scientists have probed since the beginning of the structural era in biochemistry.

I mentioned earlier that designing experiments to investigate these aspects of protein-protein interaction can be very difficult—how does one differentiate between two competing pathways, for example, which might be present at the same time in a population of dimers? One possible way would be to mutate residues at the interface, one by one, and investigate their effects on the kinetics and/or thermodynamics of interaction. This might be difficult to interpret, however, given that data are noisy and extracting the correct information about what a given residue's role is often difficult when there are complex mechanisms or competing dynamics caused by mutation. Another potential method is to directly measure time-dependent changes using some kind of spectroscopic technique. We might envision applying something like NMR or infrared spectroscopy to ascertain the evolution of spectral features, which might in turn yield insight into structural changes of our protein. However, this turns out to be extremely challenging due to the difficulty in assigning spectra (for IR), limited time-resolution (in the case of NMR), and other related problems.

An entirely alternative method to these experiments is to perform a "computational" experiment, simulating our

system using a computer and in principle revealing information at a much more detailed spatial and

time-resolution.

More specifically, a common method called molecular dynamics (see these slides for

a nice non-technical overview), or MD, models the atomic dynamics by integrating Newton's equations of motion.

Of course, when using a computer simulation, we must keep in mind that it is indeed a

Beyond the issues with incomplete modeling of physical reality, we must contend with the vast timescales of

biological events compared with those of typical simulations.

For atomistic MD simulations, the timestep (i.e. how much we integrate forward Newton's equations at every step)

is limited to a few femtoseconds (1e-15 s).

The fundamental limitation for how long an MD timestep is the fastest vibrational motions in a system, which

is around 1 femtosecond for an explicit atomistic simulation.

Nowadays, there are several algorithms which can constrain the hydrogen atoms in a protein system, enabling

slightly larger timesteps, but these are still peak around 4 femtoseconds.

To do even better than this, we need to be more tricky with how we actually perform the integration (check

out the BAOAB integrator) or by using multiple sizes of timesteps (e.g. the RESPA

algorithm).

With all these fancy tricks, we can in principle push the timestep up to around 8 femtoseconds (!).

On the other hand, many processes, including insulin dissociation, occur on the millisecond timescale or longer

(hours for some ligand-protein dissociations).

To directly observe a dissociation event would hence take approximately

With those caveats aside, however, the advantages of MD simulations are that they yield an

It turns out there's a pretty slick way of getting around the fact that we typically can (or want) to run a

bunch of short simulations rather a single long simulation (how short depends on the actual system, but for our

purposes, let's say anything less than a microsecond).

Running a bunch of short simulations also lends itself well to the massively-parallel computer architectures you

find in general-purpose supercomputers, where there's a bunch of cores packed into nodes without a ton of

interconnection.

With that in mind, here's the gist of it:

Here's a more technical description for those interested:

the specific thing (mathematical object) that we are trying to approximate from our short trajectories is

what's called the transition operator (or Koopman operator in the dynamical systems literature).

This infinite-dimensional operator tells us how

in order to study the dissociation or association process, what we really care about are the long-timescale

Performing this analysis on insulin reveals some rather interesting aspects of its dissocation. Most salient is the fact that dimer dissociation is multi-pathway, or it proceeds through multiple different mechanisms, in other words. Looking at the structure of insulin, one might postulate that there are two limiting regimes for dissociation: one where the alpha helices separate first, and one where the beta sheets separate first. These are indeed two of the pathways that appear in computational analysis, though we see a large range of intermediate pathways between the two limits. Water also plays a large role, hydrating interfacial residues as the dimer begins to separate and mediating the monomer formation. Finally, the insulin dimer occasionally rotates along the interface without completely separating, which often represents a preliminary state in dissociation.

There are many other things that I could say about insulin in particular, but the punchline is that dissociation is an extremely complex process requiring the concerted action of many atoms. Furthermore, these kinds of specific insights would have been incredibly difficult, if not impossible to extract from experiments. Of course, the natural next steps are to investigate other protein-protein systems to see if these same kinds of lessons hold true. Are all protein-protein association processes inherently heterogeneous? How does water mediate dynamics at protein-protein interfaces? These are all questions which are ripe for computational study.